On The Trail Of The “Buffalo Skinners”

by Jürgen Kloss

PART 1

“The Buffalo Skinners” is one of the most popular American “Folk songs”. It can be found in many song collections and it has been recorded and performed by a lot of singers. Its been around since the 1870s, and recorded by everyone from Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger to Willie Watson and Ricky Scaggs. Here is a history of the hand me down tune.

I’ve heard it first from Bob Dylan when he played it at a show in Den Haag in the Netherlands in 1989. This song is from the era of the so-called “great slaughter”, the extermination of the buffaloes on the Southern plains in the 1870s:

When the frontier of the United States extended to the Great Plains, among the obstacles to be overcome were the Indians and the buffalo — the former for well-known reasons and the latter because they existed in such tremendous numbers as to make farming and ranching impossible and also because they represented the commissary of the warlike Indians (Handbook of Texas Online: Buffalo Hunting).

Selling buffalo hides was for a short time a very lucrative business and countless hunters set out to get a slice of that cake. “Buffalo Skinners” tells the adventurous story of a hunting party and their troubles. In the end the boss wants to deny his men their pay, so they kill him and leave his “bones to bleach on the range of the buffalo”.

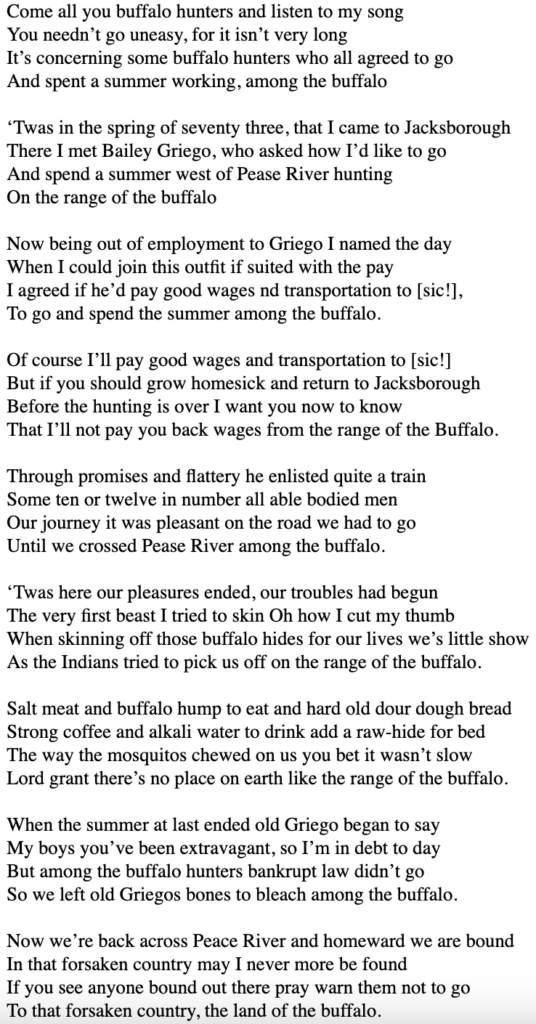

This song has a fascinating and very interesting history. Some of the most important Folklorists and popularizers of “Folk songs” were involved, for example John and Alan Lomax and Carl Sandburg. A lot has been written about this song but I tried to go back to the original sources. The story of the so-called “Folk songs” is also the story of their collectors and of those people from whom they have received the songs. Without them we wouldn’t know anything. “Buffalo Skinners” was first published by “Jack” Thorp in his Songs of the Cowboys (1908, as “Buffalo Range”, pp. 31-33). He only included a text but not a tune:

N. Howard “Jack” Thorp (1867-1940) was originally from New York City but as a boy he used to spend the summers on a ranch in Nebraska. Later he moved to New Mexico to become a cowboy and he began learning their songs. In fact he soon was “a singing cowboy who carried his banjo-mandolin with him as he rode from cow camp to cow camp” (Logsdon 1995, p. 296). He started collecting songs in 1889. “His fifteen-hundred-mile horseback journey through New Mexico and Texas in 1889-90 was the first ballad-hunting adventure in the cowboy domain” (Austin & Alta Fife in Thorp 1966, p. 6). The first edition with 23 texts was privately published and only 1000 copies were printed. There was a second edition in 1921 with 100 songs but here for some reason “Buffalo Skinners” was missing.

Thorp’s book was the very first collection of cowboy songs and he was a pioneer in that field. But his efforts were quickly overshadowed by John A. Lomax from Texas whose Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads was published in 1910 and became much more influential, in fact it turned out to be the first stepping-stone towards that massive empire of Folk song he and later his son Alan were to erect in the following decades.

Lomax – at that time a professor for English at Texas A & M – had been interested in “frontier songs” for quite a long time. A couple of years ago he had even written a short essay called “Minstrelsy of the Mexican Border”, the title of course a little tribute to Sir Walter Scott (see Porterfield, p. 60). In 1906 he spent a year of graduate work at Harvard University. At this time Harvard was the center of folk ballad research. Francis J. Child (1825 – 1896) had been professor there and his successor George Lyman Kittredge as well as Barrett Wendell kept his legacy alive. Both Kittredge and Barrett encouraged and supported Lomax who regarded the cowboy songs as indigenous American Folklore, as worthy of research and publication as the British ballads canonized by Child in his massive English And Scottish Popular Ballads:

“Kittredge expressed immediate interest in what Lomax told him about cowboy songs and suggested ways that Harvard – or at least Wendell and Kittredge – might support his efforts to increase his stock of material, which at that time apparently consisted of little more than the few verses he had published in ‘Minstrelsy of the Mexican Border’ eight years before, coupled with vague memories of songs he had heard growing up” (Porterfield, p. 115).

Lomax sent a circular to local newspapers and teachers and asked for songs. Most of what was included in Cowboy Songs was received from these kind of sources and there was not much real fieldwork. Some texts were even cribbed from Thorp’s book (see Logsdon 1995, pp. 300-302). Nonetheless he managed to publish 112 songs, among them many that would become classics of that genre, for example “Home On The Range”, “Whopee-Ti-Yi-Yo, Git Along Little Dogies”, “The Old Chisholm Trail”, “Sweet Betsy From The Pike”, “Jesse James”, “The Days Of Forty-Nine”. “In canonizing cowboy songs instead of ancient ballads, Lomax changed the face of the folk, replacing the sturdy British peasant with the mythical western cowboy” (Filene 2000, p. 32).

The “romanticization of the West” (Stanfield, p. 48) was a recent development, the “mythical cowboy” a new cultural icon. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, popular dime novels, Theodore Roosevelt’s Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1896), Frederic Remington’s paintings, Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian (1902) and the very first Western movie The Great Train Robbery (1903) all had their share in the creation of this “mythic West” that is now such an important part of American popular culture. Lomax’ collection provided the soundtrack and Teddy Roosevelt – to whom this book was dedicated – even wrote a sympathetic endorsement that was reprinted in every successive edition.

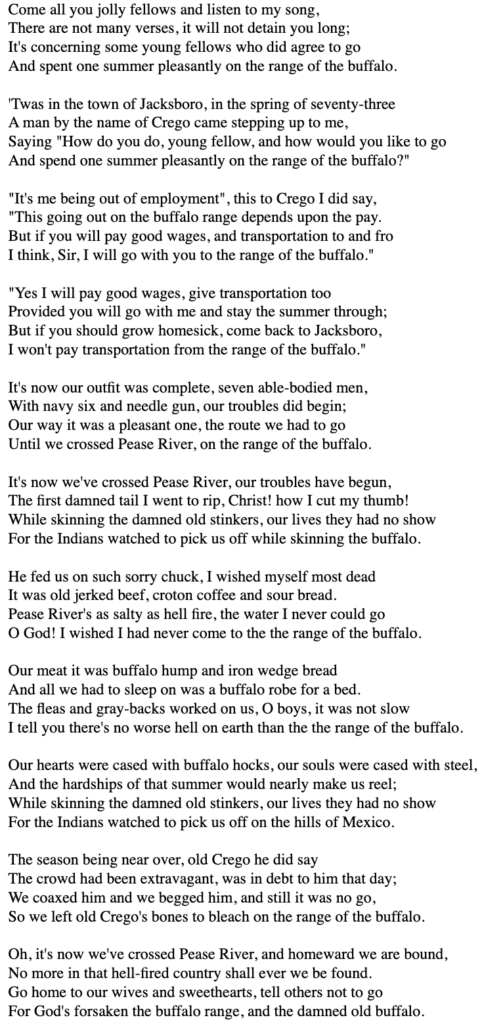

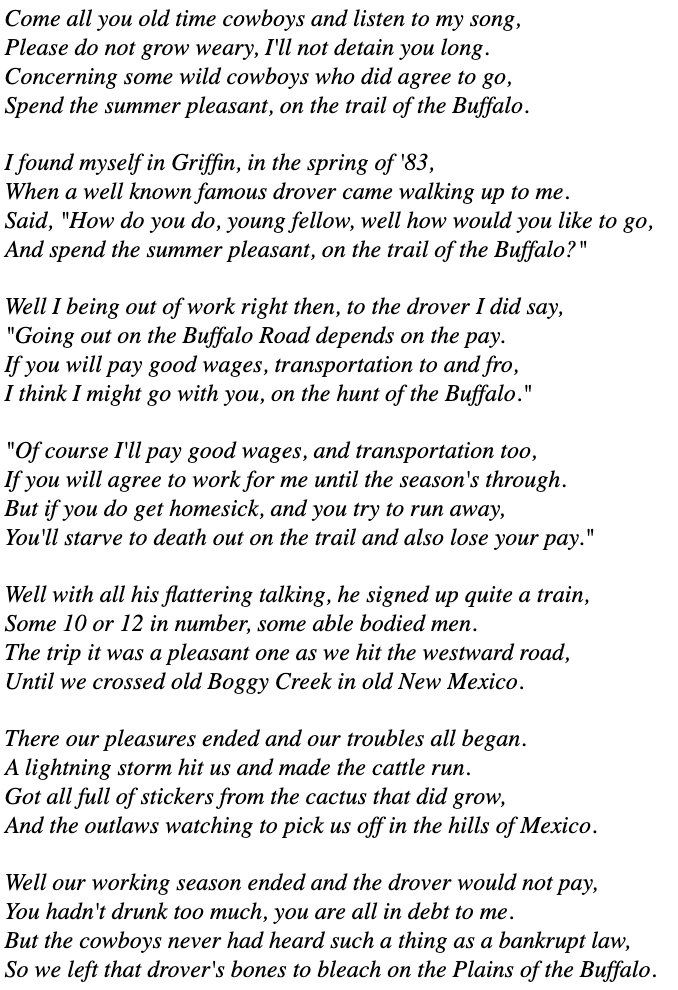

“The Buffalo Skinners” – or “Range Of The Buffalo” – in Lomax’ Cowboy Songs (pp. 158-161, tune on pp. 162/3) is slightly different from the version published by Thorp:

Unfortunately Lomax gave no contextual information. Exact scholarship á la Child and or other professional Folklorists was not his purpose and he insisted that “the volume is meant to be popular” (quoted in Stanfield, p. 47). Only in the enlarged edition published in 1938 (p. 335) he credited his source, J. E. McCauley from Seymour, Texas who had included a short note when he sent him the song:

“Song made by Buffalo Jack […] I don’t know the author or how it come to be wrote, or anything of that kind, but they must have been somebody of that name for a starter”.

According to another story included in his Adventures of a Ballad Hunter (1947, p. 54) he had heard this song from an old buffalo hunter from Abilene, Texas:

“[He] went on to tell the story of a group of buffalo hunters that he had led from Jacksboro, Texas, to that region of Texas far beyond the Pease River. The hunt lasted for several months. The plains were dry and parched. The party drank alkali water, ‘salty as hell-fire,’ so thick it had to be chewed; fought sandstorms, flies, mosquitoes, bed-bugs and wolves. The Indians watched to pick them off from near-by Mexico. At the close of the season the manager of the outfit, who had been hauling the hides to the nearest markets, announced to the men as they broke camp for the trip home that he had lost money on the enterprise and could not pay them wages. The men argued the question with the manager.

‘So,’ the old man told me, ‘we shot down old Crego, the manager and left his damn ol’ bones to bleach where he had left many hundreds of stinking buffaloes. It took us many days to get to Jacksboro. As we sat around the campfire at night, some one of the boys started up a song about our hunt, the hard times and old Crego. and we all set in to help him. Before we got to Jacksboro we shaped it up and our whole crow would sing it together. And he sang to me in nasal monotonous tone, ‘The Buffalo Skinners’ […]”

This of course sounds more like the typical Folklorists’ yarn. But interestingly here he also claimed that he had collected “twenty-one separate versions from all over the West” from which he then collated his text.

PART 2

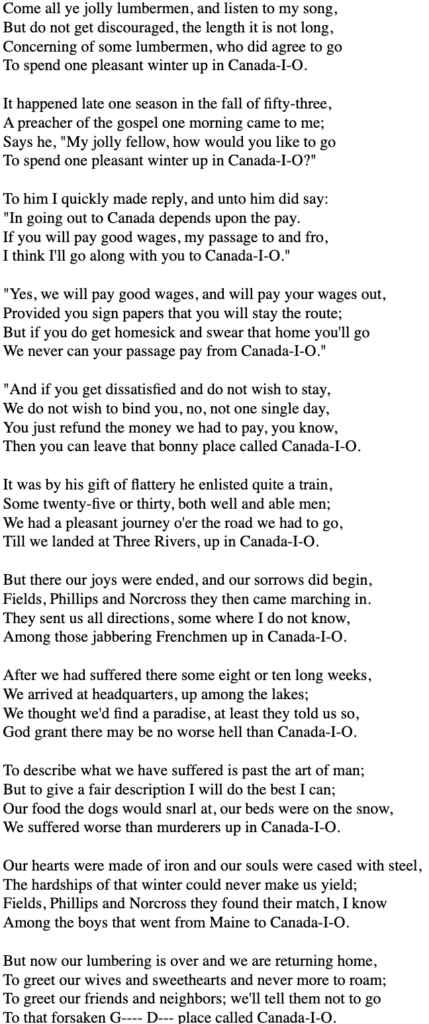

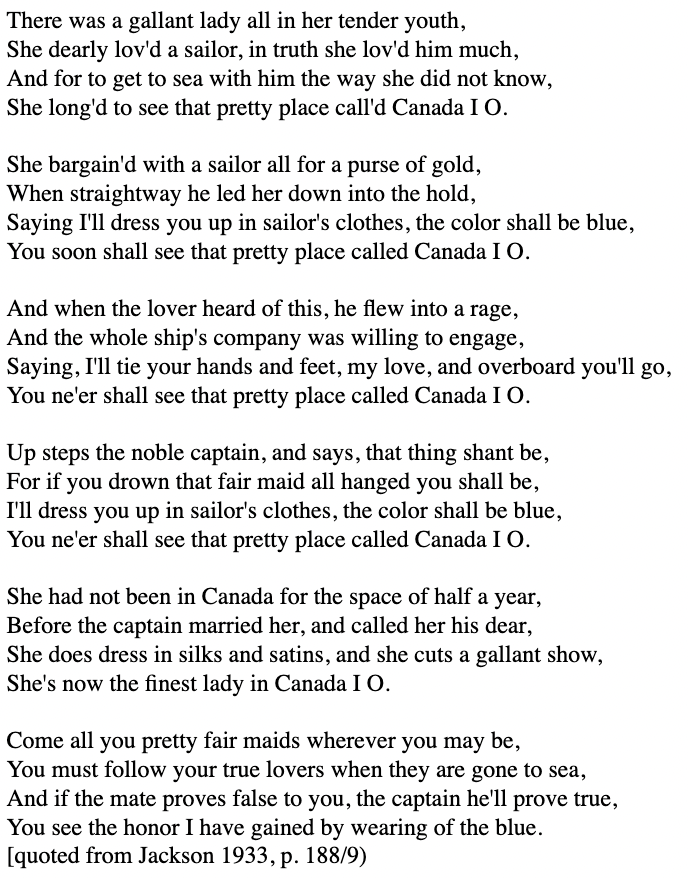

“Buffalo Skinners” is not an original song from Texas. This was first noted by writer and Folklore collector Fannie Hardy Eckstorm (1865-1946) from Maine. In 1914 she met John Lomax at one of his lectures and pointed out to him that it was “only a variant of our own ‘Canaday I O'” (Eckstorm/Smyth 1927, p. 21), an older local ballad about a group of lumberjacks and their exhausting trip to Canada. Ms. Eckstorm had heard this song in her childhood and in 1904 she found a fragmentary version (see dto , p. 24, first published in Gray 1924, p. 37-39). Only in the twenties she managed to get hold of a complete text. It was sent to her by one Annie Marston who “had learned it in her youth”. This set of lyrics was first printed in 1927 in her collection Minstrelsy of Maine (Eckstorm/Smyth 1927, p. 28/9):

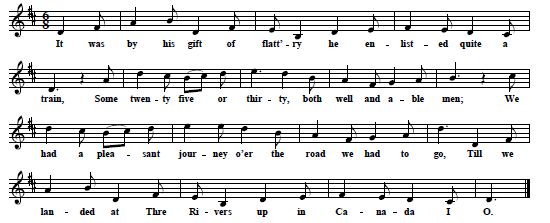

Later, in a short article for the Bulletin of the Folksong Society of the Northeast (Eckstorm 1933, p. 10), she published the tune:

|

Mrs. Marston had also sent her some interesting information about the song and its writer:

” […] this song was composed by Ephraim Braley, a lumberman who lived in Hudson, Maine, the town on the west line of Oldtown. She remembers him as a man of about her fathers age, a good singer with a comic and highly satiric turn, who made up many songs about local people and events. In 1853 he and other local men hired out to Fields, lumbermen, to go to Three Rivers, P.Q., to work in the woods […] The song, composed after the return of the men in the spring, commemorates their experiences” (dto., p.11) .

It seems that “Canaday I O” is based on the “Canadee-I-O”, a ballad known at least since the 1830s and printed regularly on British broadsides:

- “Kennady I-O” (between 1813 and 1838, Harding B 11(1982))

- “Canada, I O” (between 1849 and 1862, Harding B 11(2920))

- “A Lady’s Trip to Kennedy” (undated Firth c.12(330),all at the allegro Catalogue of Ballads)

This song was also popular in North America and it could be found for example in the Forget-Me-Not Songster, a “choice collection of old ballad songs, as sung by our grandmothers. Embellished with numerous engravings”, printed a couple of times since 1845:

Some versions were also collected from oral tradition in Canada – see this one from Labrador at the Digital Tradition Database – though not in the USA. But according to Ms. Eckstorm “Canadee-I-O” was “much sung in Maine, both in the woods and elsewhere” (Eckstorm/Smyth 1927, p. 25). Of course the lyrics are completely different. Braley only retained “Canada-I-O” at the end of each verse. Also the melody for the British ballad as given by Ms. Eckstorm – it’s very different to the tunes used today, for example by Nic Jones on Penguin Eggs (1980) and Bob Dylan on Good As I Been To You (1992) – is only very loosely related to the one used by Mrs. Marston for the Maine song. But the phrase structure is very similar and it’s in fact possible to sing the lyrics of “Canada-I-O” to the melodies used for the British “Canadee-I-O” and vice versa. It sounds a little strange but it works!

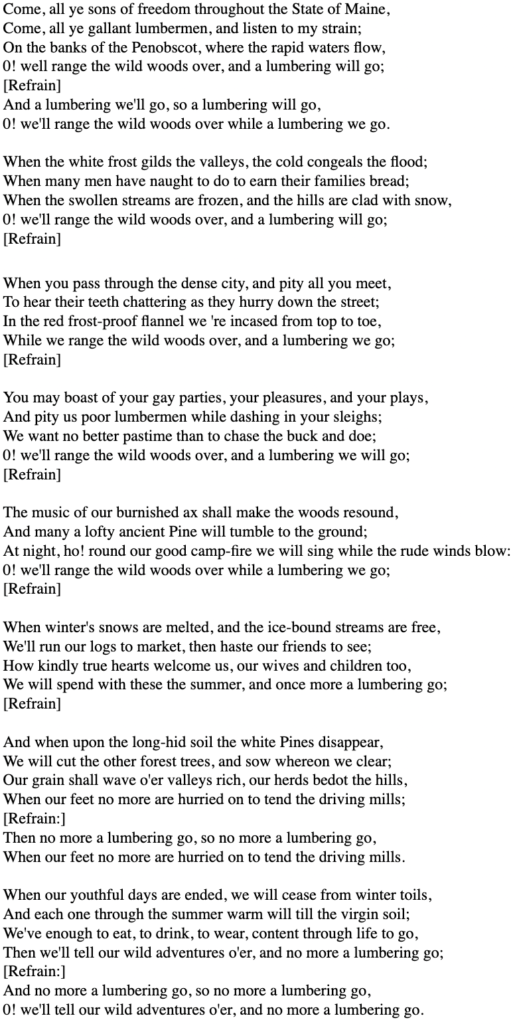

There was another song that also could have served as a kind of inspiration or framework for Mr. Braley when he put together “Canaday I O”. In 1851 John Springer published Forest Life And Forest Trees, a book about lumbering in Maine and New Brunswick. He included the words to “The Logger’s Boast”, a romantic celebration of the work and life of the lumbermen “composed by one of the loggers” (pp. 132-3). One may assume that it was at that time well-known among the woodsmen in Maine. “Canaday I O” looks like a deliberate parody of this song:

We only know about Ephraim Braley from Mrs. Marston. Otherwise nothing else is known about him. He is mentioned nowhere else and no other songs known from Maine are ascribed to him. Also the song’s purpose is not clear: was it a protest against working conditions, an adventurous story about tough lumbermen or perhaps in fact a humorous parody of “The Logger’s Boast”? Not at least is there no way to know how popular Braley’s song really was at that time. Ms. Eckstorm claims that it was “once sung by every lumberman in the Maine woods” (Eckstorm/Smyth 1927, p. 22). That leaves the question why she or other collectors haven’t found more complete variants besides this one and two fragmentary versions. The second fragment can be found in E.H. Linscott’s Folk Songs of Old New England (1939, pp. 181-183, from Sam Young of North Anson, Maine who “sang this song in Maine lumber camps fifty years ago”)

But “Canaday I O” quickly migrated to other states and Folklorists have found some localized variants. H. W. Shoemaker collected a Pennsylvanian version, “The Jolly Lumbermen”, in 1901 and published it in 1919 in his North Pennsylvania Minstrelsy (pp. 76-78; see also Gray 1924, pp. 41-43 ). Interestingly he regarded it as a variant of “The Logger’s Boast”

Come, all you jolly lumbermen, and listen to my song;

But do not get uneasy, for I won’t detain you long.

Concerning some jolly lumbermen who once agre[e]d to go

And spend a winter recently on Colley’s Run, i-oh!We landed in Lock Haven, the year of seventy-three.

A minister of the Gospel one evening said to me,

Are you the party of lumbermen that once agreed to go

And spend a winter pleasantly On Colley’s Run, i-oh?

[…]

In 1913 George F. Will published “Shanty Teamster’s Marseillaise” in the Journal of American Folklore (pp. 87/88). This variant about the teamsters in lumber camps in the Opeongo Hills in Ontario included an additional chorus and was obviously regarded as a “comic song”. Will’s informant had “heard it sung on various occasions during my four winter’s shantying in that region, between the Bonne Chere and the Madawaska in Ontario. And that was during the years 1871 – 1876”:

Come, all ye gay teamsters, attention I pray,

I’ll sing you a ditty composed by the way,

Of a few jovial fellows who thought the hours long,

Would pass off the time with a short comic song

[…]

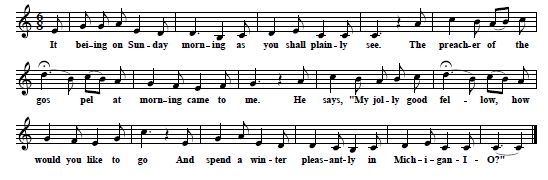

“Michigan-I-O” is about lumberjacks from “Kennedy” spending a hard winter in Michigan. A variant “Sung by Mr. Arthur Milloy, Ornemee, North Dakota” was included in Franz Rickaby’s Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy (1926, No. 8, pp. 41/42):

|

Three more versions are available in Gardner & Chickering’s Ballads and Songs of Southern Michigan in 1938 (No. 105, pp. 261-3):

It was early in the season, in the fall of sixty-three,

A preacher of the gospel, why, he stepped up to me.

He says, “My jolly good fellow, how would you like to go

And spend a winter lumbering in Michigan-I-O ?”I boldly stepped up to him, and thus to him did say,

“As for my going to Michigan, it depends upon the pay.

If you will pay good wages, my passage to and fro,

Why, I will go along with you to Michigan-I-O.”[…]

O now the winter is over it’s homeward we are bound,

And in this cursed country no more we shall be found.

We’ll go home to our wives and sweethearts, tell others they must not go

To that God-forsaken country called Michigan-I-O. [version A]

“Way Out In Idaho” is at least partly related to this song family and different versions have been collected and printed since 1923 (see Cohen 2000, p. 560-565). Here are the first two verses and the additional chorus from Lomax’ collection Our Singing Country (1941, p. 269/270)

Come all you jolly railroad men, and I’ll sing you if I can

Of the trials and tribulations of a godless railroad man

Who started out from Denver his fortune to make grow,

And struck the Oregon Short Line way out in Idaho.[Chorus]:

Way out in Idaho, way out in Idaho,

A-workin ‘on the narrow-gauge, way out in Idaho.I was roaming around in Denver one luckless rainy day

When Kilpatrick’s man, Catcher, stepped up to me and did say,

“I’ll lay you down five dollars as quickly as I can

And you’ll hurry up and catch the train, she’s starting for Cheyenne.”

[…]

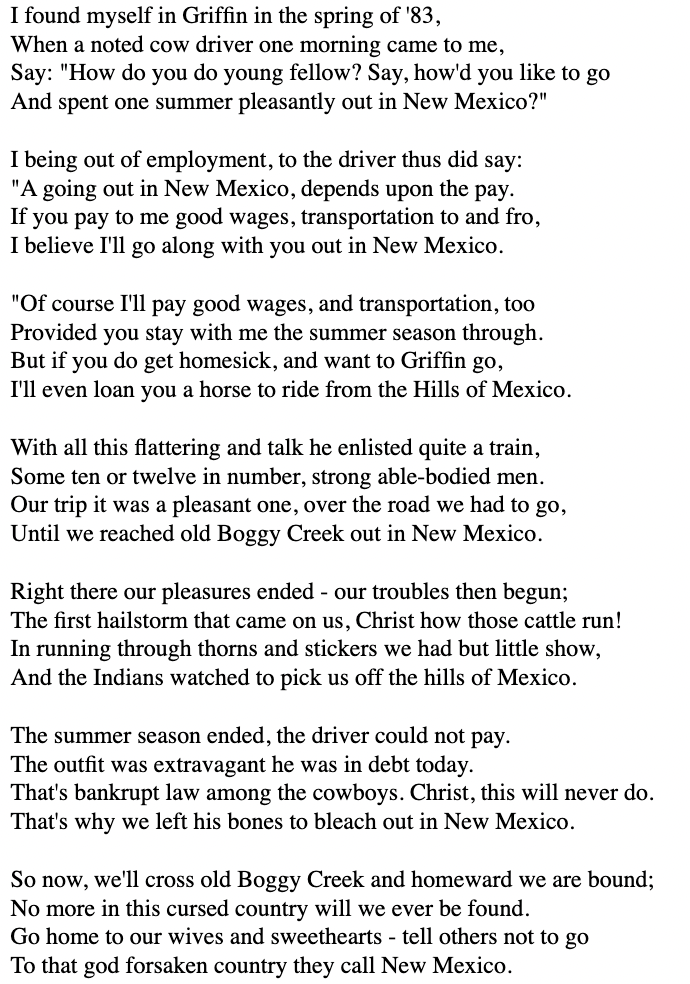

To make matters more complicated there are also three cowboy versions. “The Hills Of Mexico” is clearly derived from “Buffalo Skinners”. John Lomax had collected a couple of variants (see Thorp 1966, p. 217) but he didn’t include it the early editions of his Cowboy Songs. It was first published as “Boggus Creek” in 1923 by W. P. Webb (in Dobie, Coffee In The Gourd, p. 45, online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library). Unfortunately this variant is incomplete and the last verses are missing.

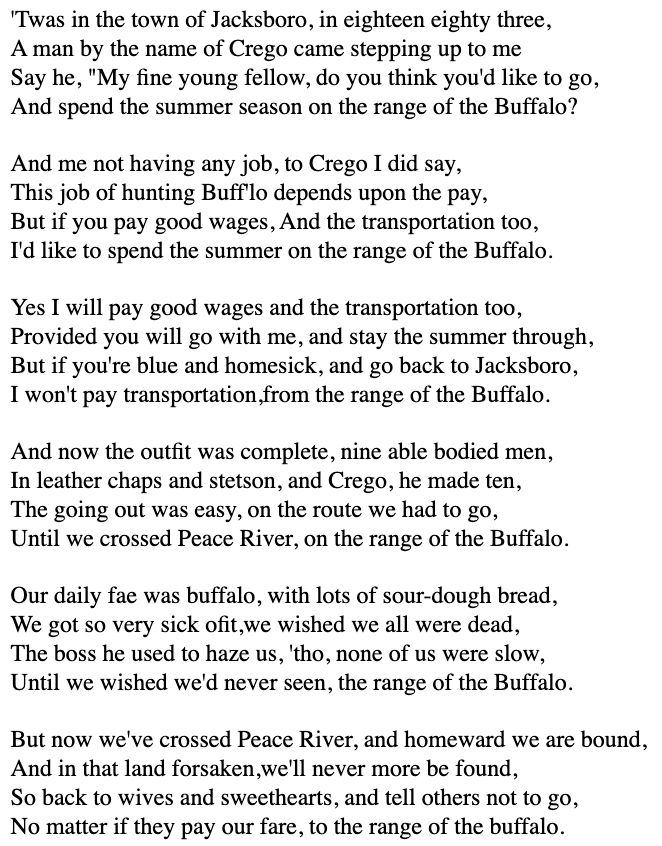

J. Evetts Haley found a complete text in 1927. He got this song from James “Honey Jim” Mullens, an old cowboy whom he described as a “human anthology of western ballads […] all his knowledge of the field had been gained from oral sources”. Mullens had learned it “in the early eighties […] while driving over [the] Goodnight-Loving Trail with a cowman from Mason County” (Haley 1927, pp. 201-3, online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library):

In 1938 John and Alan Lomax published another complete text – as “Boggy Creek” – in the new enlarged edition of Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads (p. 41/2). Unfortunately they didn’t give any contextual information except that they had received it from “H. Knight, Sterling City, Texas”. This version is virtually identical to the one unearthed by Haley. But here the introductory verse is included:

Come all you old-time cowboys and listen to my song,

But do not grow weary, I will not detain you long;

It’s concerning some cowboys who did agree to go

To spend one summer so pleasantly on the trail to Mexico

Also the last line of the 4th verse is different. Instead of “I’ll even loan you a horse to ride […]” it’s the opposite: “I will not furnish you a horse to ride […]” but that is of course more true to the corresponding line in “Buffalo Skinners”.

There are also two field recordings that I haven’t been able to check out: one by Alec Moore that was recorded in 1934 in Austin by John Lomax (LOC, John Lomax Southern State Collection, AFS 00057 A01) and one by Mamie Reed from Kentucky (1940, Mary Elizabeth Barnicle-Tillman Cadle Collection, Archives of Appalachia, E. Tenn. State Univ., Disc BC-345; Roud# S273394). In 1950 John Donald Robb found a localized variant from New Mexico called “Murphy’s Farm” (J. D. Robb Collection, University of New Mexico, MU7 CD 14 Track 9). Alan Lomax included another version – “On The Trail To Mexico” – in The Folk Songs of North America (p. 380) but that was his own adaptation of Mr. Knight’s “Boggy Creek” from the 1938 edition of Cowboy Songs.

Then there is “The Crooked Trail To Holbrook” (Lomax 1910, pp. 121-123; Thorp 1921, pp. 53/4), a variant from Arizona that is loosely based on the same model. It’s another story about a difficult cattle drive. One line in the fourth verse – “[…] Christ, how the cattle run” – strongly suggests that this song was derived from “The Hills of Mexico”. Some other phrases have survived too, for example in the last verse “homeward we are bound” and the “wives and sweethearts”. Apart from that there are not much similarities except the structure: no trouble with the boss, no dangerous Indians: “across the reservation no danger did we fear”.

“John Garner’s Trail Herd” (Lomax 1910, pp. 114-16; Thorp 1921, pp. 84-86) seems to be member of this song family, too. But there are even less parallels to the others. According to Thorp it was “written by one of the waggoners at Fort Worth, Texas, many years ago. I first heard it sung in the Spearfish Valley, Dakota”. Interestingly both songs are only known from the versions published in Lomax’ and Thorp’s books, which are in both case very similar to each other. To my knowledge no more variants from oral tradition have been found.

Both Eckstorm (p. 12) and Welsch (pp. 109, 115) think that the dissemination of this song family shows clear signs of what is called “multiple diffusion”. All major localized variants – “Jolly Lumbermen”, “Michigan-I-O”, “Way Down In Idaho”, “Buffalo Skinners” – seem to have derived directly from Mr.Braley’s “Canaday I O”: “[…] the song passed westward by three different leaps, each one from Maine, and got to different sections of the country […] the case is one of distribution from a focal point, not by drift” (Eckstorm 1933, p. 12). This sounds reasonable but the available evidence is of course extremely fragmentary and we are walking on very thin ice here. We know that these songs have existed in oral tradition but not how and by whom they were carried to other places.

PART 3

We don’t know how “Canada-I-O” traveled from Maine to Texas but it seems we know who has written the original “Buffalo Skinners”. In 1941 Texan Folklorist J. Frank Dobie had an interesting encounter:

“In the late summer of 1941 M. A. Tracy of Dallas brought John B. Freeman, his father-in-law, to talk with me and sing me a song that he had composed sixty-three years back and now wanted to get copyrighted and put into circulation. He called it “The Buffalo Song,” and as soon as he started to sing it I was convinced that it was the original version of “The Buffalo Skinners” so popularized by Lomax, Sandburg, and others. He had however, never heard the popularized version, had no idea that any form of the song had been put into print. He told me how, when and where he composed the song” (Dobie 1943, p. 2, online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library).

Freeman had moved to Texas from Tennessee in 1872 at the age of 15. Five years later in the fall of 1877 he was hired in Fort Griffin by a professional hunter named James Ennis. Ennis was no fictional character, a buffalo hunter with this name really did exist (see the story in Gard, p. 284). Freeman and another fellow had to skin the buffaloes and the party also included a cook. The trip lasted a whole year: “I made up my song little by little while we were on the buffalo range, keeping it in my head […] I had it all finished before we finally headed in for Fort Griffin, leaving the last buffalo behind us. I remember when we crossed the Brazos one of the other boys said, ‘Well, you’ve got a good song out of the trip anyway.'” (Dobie 1943, p. 2/3):

|

Although his trip was in 1877/78 Freeman “gave the date as ’73, I had to do that in order to rhyme with ‘me'” (Dobie 1943, p. 3). It seems he tried to retain as much as possible from the second verse of “Canada-I-O”. But it’s also important to know that 1873 “was a bit early for hide hunting in Texas” (Gard 196, p. 291):

“I don’t think there was any organized buffalo hunting on the on the Texas plains as early as 1873. The Indians were too bad. The battle of Adobe Walls, just north of the Canadian River, wasn’t until June 1874 […] By 1877, when we went out, the Comanches and Kiowas had been rounded up” (John B. Freeman quoted in Dobie 1943, p. 3/4).

In fact the “great slaughter” of the buffaloes on the Southern plains “began in earnest in 1874 and was over by 1878” (The Handbook of Texas Online: Buffalo Hunting). In December 1877 and January 1878 “a hundred thousand” buffaloes were killed “on the Texas ranges alone” (Clayton, p. 86). In the winter of 1878 the hunters had already problems finding them. At the end of decade they were more or less extinct in Texas and the hunters and skinners had to search for another job or move to the Northern plains.

Freeman “minimizes the hardships of this hunting trip”, his song “depicts the very opposite of the reality” (Welsch, p. 114). The food was good, the cook was very competent and the Indians were no problem: “Once in a while a few Indians would come to the camps, but they were peaceful. I was thinking about the old days when I put them in the song as ‘watching to take our scalps” (quoted in Dobie 1943, p. 4).

What distinguishes “Buffalo Skinners” from “Canaday I O” and its other off-springs is the penultimate verse about the conflict between the workers and the boss who “swore he could not pay” because “the outfit had been so extravagant that he was in debt that day”, “a vast improvement” to the this song as it turns a “series of complaints” into a drama (A. Lomax 1960, p. 360). But this story was also made up by Freeman:

“In the song I made out that Ennis was trying to beat us out of our pay just as a joke on him. He was fair and square and we all liked him; he would laugh when I sung that part of the song” (Dobie 1943, p. 4).

Interestingly in this version the workers only take the hides but they do not kill their boss as in the other variants of this song. This seems to be a later addition. Another dateable early text (here as pdf) of “Buffalo Skinners” was published by Robert W. Gordon in 1924 in the Adventure Magazine. He had received it from someone who “sang the ballad on the Chisholm Trail in the early 1880s” (Friedman 1977 [1956], p. 429/30). Here this motif is already included:

The season being ended, Old Crigor could not pay –

The outfit was so extravagant he was in debt that day –

But among us jolly bull-skinners bankruptcy will not go,

So we left poor Crigor’s bones to bleach on the Range of the Buffalo.

It’s also part of “The Hills of Mexico”, as here in the version James Mullens had learned “in he early eighties” (Haley 1927, p. 202):

[…]

That’s bankrupt law among the cowboys. Christ, it will never do.

That’s why we left his bones to bleach out in New Mexico.

It seems that someone modified the original version shortly after it had been written – between 1878 and 1883 – by introducing this motif. In fact it is a very effective change: the bosses bones are bleaching among those of the buffaloes he has killed. This text then must have been the point of origin for all later variants of both “Buffalo Skinners” and “The Hills of Mexico” – at least those we know. But it’s also possible that this line was first invented for the cowboy version – because here taking the hides would make no sense – and then migrated back to “Buffalo Skinners”. But of course that’s only speculation and most likely we will never know.

On the other hand it’s important to note that the most effective line of this song wasn’t included at first and only added later by an anonymous editor. Austin and Alta Fife (in Thorp 1966, p. 205) quote other even more graphic variants of the second half of the penultimate verse. Unfortunately they don’t identify the sources but to me they look like they are from later incarnations of this song:

[…]

We tripped him and we kicked him to make the money flow

We left his pesky hide to bleach with the bones of the buffalo[…]

But the skinners clubbed together and said that did not go

So we left old Trego’s bones to bleach with the bones of the buffalo.

Today we tend to believe that “Buffalo Skinners” is telling a true story or that it’s even some kind of protest song. But a song is not supposed to tell the “truth”, whatever that is. This song is a romanticized image of a trip that had consisted mainly of hard work. The food was OK, the Indians didn’t harm them, the boss was nice and the money was good, the only problem was that there were no girls (see Dobie 1943, p. 3). That’s boring, isn’t? So the writer has turned it into a dramatic fantasy of how it could have been. Maybe it was even intended as a humorous parody. Obviously Mr. Ennis didn’t regard this song as a threat to his reputation although it tells that he tried to cheat his workers out of their money. So maybe they knew all it was a joke and not a protest against the boss.

I see no reason to doubt the authenticity of Freeman’s text, not at least because it is much closer to “Canada-I-O” than Lomax’, Thorp’s and Gordon’s versions and he definitely must have known it. Unfortunately Dobie doesn’t tell us if he had asked him about Braley’s song. Welsch (p. 114) seems to think that James Ennis himself may have been the source as he was from Canada but I presume we’ll never find out.

There are some important differences to the other available variants of this song that are worth discussing. Thorp, Lomax and Gordon have Jacksboro as the town where the story starts. But that must be a later addition. Freeman met Ennis in Fort Griffin and at this time Griffin was the “capital of the buffalo hunting world” (Dobie 1943, p. 3):

“Fort Griffin, the frontier town on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, was headquarters for the buffalo hunters during the great slaughter. It was the wildest and the most colorful of all the bordertown […] Fort Griffin was the last town with any semblance of civilization on the western frontier of Texas, and that semblance was very thin […] The buffalo hunters and the skinners, fresh from a womanless country farther west, flocked to Fort Griffin for a fling, their pockets bulging with money” […] During the extermination of the buffalo it was necessary to go to Fort Griffin for various and sundry reasons. We sold our hides there, and we hauled out supplies from there” (Collinson/Clark, p. 84; for more about this town see also The Legends of America: Fort Griffin – Lawlessness on the Brazos and Handbook of Texas Online: Fort Griffin)

Why this was later changed to Jacksboro is not clear, maybe because Fort Griffin had been closed by the army in the eighties and lost its relevance. I haven’t found any evidence that Jacksboro had ever served as a starting point for buffalo hunting parties. It should also be noted that the known texts of “The Hills of Mexico” have retained Fort Griffin: “as the buffalo were hunted out, the cowboys came. The Great Western Trail ran through Fort Griffin and straight upcountry to Dodge City” (quoted from Forttours.Com: Clear Fork/Fort Griffin)

Just like the lumberjacks in “Canaday I O” the buffalo hunters in Freeman’s text start their trip in the fall and spend the winter on the plains while Lomax, Thorp and Gordon say it was in the spring and summer. But Freeman’s real trip also began in the fall and and it was of course much more profitable to hunt the buffaloes during the winter because the hides were much thicker and brought much more money. Interestingly a text published in the Frontier Times in 1925 (p. 39; from “Dot Babb, Amarillo, Texas”) also claims this all happened in the winter and the second half of the first verse is nearly identical to the respective lines in Freeman’s text:

It’s concerning some buffalo skinners who did agree to go

And spend the winter pleasantly among the buffalo.

Also the name James Ennis was quickly dropped from the song. In the available versions of “Buffalo Skinners” I know of the boss happens to be someone called “Crego” (Lomax), “Bailey Criego” (Thorp), “Crigor” (Gordon), “Craig” (Frontier Times) or “Ira Crago” (in a version collected between 1940 and 1964, available in Moore 1964 and reprinted in Welsch, p. 125/6, here as a pdf; Fife in Thorp 1966, p. 200, n18 lists even more variants of that name). It’s not clear if this was a real person (see Gard 1960, p. 191). Interestingly the “noted cow driver” in “The Hills of Mexico” remains anonymous.

These are the major differences to Mr. Freeman’s original text that can be found in all available versions of “Buffalo Skinners”:

- the workers kill their boss instead of only taking the hides as payment;

- the town is Jacksboro instead of Fort Griffin;

- the trip starts in the spring not in the fall and the working season is the summer instead of the winter (except in the text from the Frontier Times where the “winter” is retained);

- the name of the boss is Crego or some variation thereof;

I’m tempted to speculate that these modifications – maybe except the change from winter to summer – were introduced to the song at a very early stage. This revised version must have been the starting point for the further dissemination of this song while Freeman’s original seems to have vanished. It’s not clear if this happened before or after the creation of “The Hills of Mexico” or if the cowboy variant had some influence on later versions of “Buffalo Skinners”. At least it should be noted that Lomax even used a line from this song in his version at the end of his ninth verse where the “Indians waited to pick us off on the Hills of Mexico”.

There are also a lot of minor discrepancies between the different versions of “Buffalo Skinners” that are worth examining. Every time a song or a story is transmitted orally the singer or storyteller may change the text. Often the reason for these changes is simply that he has forgotten something. So a line may be dropped completely or it may be replaced by something else that sometimes makes no sense. Not everybody has a perfect memory and this is especially important when a collector gets a text from someone who had learned it some decades ago.

The collector himself plays an important role, too, especially if he only is able to get fragmentary versions and then tries to collate a more complete text. John Lomax for example was notorious for editing texts before publishing because he was more interested in producing singable songs for public consumption than academic collections.

I was able to examine five variants of “Buffalo Skinners” that are distinctively different from each other and seem to be collected from oral tradition. It may be useful to list them here in order of the publishing date:

- Thorp’s was published in 1908 but it’s not known when he had collected this text.

- Lomax’ version was printed in 1910 and he later told different stories of where he had got it from;

- R. W. Gordon published his text in 1924 in the magazine Adventure where he had a regular column. His informant claimed to have learned the song in the “early eighties”.

- Frontier Times published a text in 1925 (p. 39): from “Dot Babb, Amarillo, Texas”, but they don’t say when it was written down;

- Ethel and Chauncey O. Moore found one more variant some time between 1940 and 1964 and included it without any contextual information in their collection Ballads and Folksongs of the Southwest (1964).

In case of Lomax and Thorp it is not known if and how much they have edited their texts or if they have collated them from different versions. The Moores’ variant is a little bit chaotic as if their informant had serious problems remembering the song. On the other hand it seems to me that it’s not derived from any printed source.

In 1934 John Lomax recorded in Richmond, Texas a very short and extremely mutilated version of “Buffalo Skinners” by Pete Harris that is of no help here (available on The Deep River of Song, Rounder CD 1821). According to the Roud Index two more variants are stored in archives, but they never have been published and they are not from Texas: a text collected in Virginia 1938 (Roud# S249726) and a recording from New Hampshire (1945, Roud# S272660). Even more texts from manuscripts and field recordings – mostly from Lomax’ collection – that have never been published are listed by the Fifes (in Thorp 1966, p. 216) but of course it was not possible for me to investigate them.

All other printed and recorded versions of “Buffalo Skinners” that I have seen – although I wasn’t able to check all mentioned by the Fifes (in Thorp 1966, p. 215/6) – are derived from earlier books and recordings and most of them can be traced to Lomax who was mostly responsible for this song’s further dissemination.

The five different versions of “Buffalo Skinners” examined here – Thorp, Lomax, Gordon, Frontier Times and Moore – all have retained different elements – a word, a line, a phrase or a motif – from Freeman’s text and left out others. For example the first two lines in Freeman’s eighth verse are these:

Our souls were cased in iron, our hearts were cased with steel,

The hardships of one winter’s work could never make us yield.[…]

This is nearly identical to “Canada-I-O”:

Our hearts were made of iron and our souls were cased with steel,

The hardships of that winter could never make us yield;

In Lomax’ text this couplet is turned into:

Our hearts were cased with buffalo hocks, our souls were cased with steel,

And the hardships of that summer would nearly make us reel;

[…]

Here the first line makes even less sense than the one in the original. The other versions – Thorp, Gordon, Frontier Times and Moore – don’t have these lines. I presume they were dropped some time before these texts were collected because the singers simply didn’t know what it was supposed to mean. Interestingly some other versions of “Canada-I-O” have retained this idea. Shoemakers “Jolly Lumberman” (Gray 1924, p. 69) collected in 1901 includes another corrupted variation:

Our hearts are clad with iron, our soles [sic!] were shod with steel.

But the usages of that winter would scarcely make a shield.

[…]

A version of “Michigan-I-O” collected in 1935 (Gardner/Chickering 1939, p. 262) is much closer to the original:

Our hearts was cased in iron, and our souls were bound in steel;

The hardships of that winter could not force us to yield;

[…]

This is a fine example of how two lines of a song can be changed in different ways when transmitted orally. In “Canaday I O” the second verse is:

It happened late one season in the fall of fifty-three,

A preacher of the gospel one morning came to me;

Says he, “My jolly fellow, how would you like to go

To spend one pleasant winter up in Canada-I-O?”

Freeman’s text has retained as much as possible from the the song that had served as its model:

I happened into Fort Griffin early in the fall of ’73

When James Ennis by name one morning came to me,

Said, “My jolly young fellow, how would you like to go,

And spend one winter pleasantly amongst the buffalo.

This is closer to “Canaday I O” than all the other variants of “Buffalo Skinners” where we can find different kinds of variants of this verse. But they all leave out the phrase “one morning”. On the other hand it’s included in Mullens’ “The Hills of Mexico” (“[…] when a noted cow driver one morning came to me”) so it must have also been part of the very early versions of “Buffalo Skinners”. And in the text from the Frontier Times the boss at least greets his future employees with the words: “Good morning, young fellows”.

In “Canaday I O” the “preacher of the gospel” manages to enlist his men “by his gift of flattery”. In Freeman’s text it is changed to:

With all such flatterations we [sic!] enlisted quite a train

The word “flatteration” is very unusual, it can’t be found in any dictionary and it has been used very rarely. I presume Freeman simply made it up. In Thorp’s version it is turned into “through promises and flattery”, in Mullens’ “Hills of Mexico” it’s “flattering and talk”, Lomax drops it completely but surprisingly Gordon’s version has retained this artificial word:

By such talk and flatteration he enlisted quite a crew

I have searched Google Books for this word and found exactly five cases for its use from the 19th century. Two of these are the texts for Gordon’s and Freeman’s “Buffalo Skinners”. This may be taken as evidence that the word “flatteration” had in fact been included in early versions of this song and it may be one more proof for the authenticity of Freeman’s version.

In the last verse Freeman crosses the “Brazos River and homeward we are bound”. In Thorp’s and Lomax’s versions the Brazos is replaced by the Pease River, in the Frontier Times and in Moore’s it’s the Wichita. The text published by Gordon retains the Brazos. Interestingly John J. Callison’s Bill Jones of Paradise Valley, Oklahoma (1914, p.117/18) quotes – in a story about Buffalo Bill – two verses from what looks like another early variant and here it’s also the Brazos River:

And now we are across the Brazos, and homeward we are bound;

No more in that cursed country will ever we be found;

We will go home to our wives and sweethearts tell others not to go

To that god forsaken cactus country way out in Mexico.

This strongly suggests that the Pease River was a later addition – maybe because it was already mentioned earlier in the song – while the Brazos seems to have been the original river of this verse.

Even the version collected by the Moores seems to have saved some elements from Freeman’s lyrics that can’t be found in the other texts. The last line of his 8th verse is:

For the Indians watched to take our scalps while skinning them buffalo

In Thorp’s version “the Indians tried to pick us off on the range of the buffalo”, in Gordon’s and Lomax’ variant half of the original line is still there: “the Indians watched to pick us off while skinning them buffalo” but the Moores’ informant had this line more or less complete and is the only one to mention that the Indians were eager to scalp the poor skinners:

For the Indians watched to scalp us, while skinning the buffalo

On the other hand the phrase “pick us off” is also included in “The Hills of Mexico”. So this may also have been an early change predating the creation of the cowboy variant while what was possibly the original line is only retained in the latest collected version.

I could easily add more examples. This may look like a severe case of nitpicking but a careful comparative analysis all the available texts is instrumental for any attempt to reconstruct the song’s development. Of course it’s still guesswork or more like a jigsaw puzzle where a lot of important parts are missing.

Nonetheless it’s possible to draw some conclusions: the five variants published by Thorp, Lomax, Gordon, the Frontier Times and the Moores obviously have reached the collectors on different routes of oral transmission. Gordon’s has retained some elements the earliest version while the others seem to represent later stages in the song’s develoment. “The Hills of Mexico” is occasionally closer to Freeman’s “Buffalo Song” than all the five “Buffalo Skinners”. Freeman’s text in turn is has much more similarities to “Canada-I-O” than all the other versions of “Buffalo Skinners” so it really seems to be a very early or even the earliest version.

In fact I think there’s much evidence that Mr. Freeman was the originator of this song. His story makes sense, it fits well into the historical context and his text is not only more consistent than the others. It also fits perfectly well into the blank space between “Canaday-I-O” and all the later variants of both “Buffalo Skinners” and “The Hills of Mexico”. On the other hand his original lyrics seem to have vanished very quickly from oral tradition and instead a revised version with some major modifications must have taken its place.

PART 4

It’s not known how widespread “Buffalo Skinners” was in Texas in the first years of its existence. John Lomax’s claim to have collected “twenty-one separate versions from all over the West” (Lomax, Adventures, p. 55) suggests a certain popularity. But at the time it was collected first it surely wasn’t sung anymore around every campfire. It’s more likely that it simply was one more old song only remembered by some old-timers that was on the way to fall into oblivion.

It was John Lomax himself who saved it from obscurity – Thorp’s book obviously had much less influence – and turned it into a modern “Folk Song”, a song that is better known among the Folk-fans and Folklorists than among the “Folk” itself. It’s for example amusing to read that even John B. Freeman, most likely the originator of this ballad, seems to have been completely unaware of it’s newfound popularity (see Dobie 1943, p. 2).

Lomax genuinely liked this song and performed it regularly on his lectures throughout the USA. Also Carl Sandburg – another great popularizer of “old Folk Songs” – picked up “Buffalo Skinners” from Lomax. They met in Chicago in 1920 and Sandburg was very impressed when he heard him sing this song: “That’s a novel – a whole novel – a big novel – It’s more than a song” (quoted in Adventures, p. 88). He included it in his American Songbag (1927, p. 270) where he introduced the song with a somehow bombastic comment:

“This is one of the magnificent finds of John Lomax for American folk song lore. It is the framework of a big, sweeping novel of real life, condensed into a few telling stanzas […] We may hunt for a harder sardonic than that of Crego telling the man they had been ‘extravagant’ and were in debt to him. They killed him; it is told as casually and as frankly as the doing of the bloody deed and their immediate forgetfulness about it except as one of many passing difficulties of that summer. Lomax speaks of this piece as having in its language a ‘Homeric quality.’ Its words are blunt, direct, odorous, plain and made-to-hand, having the sound to some American ears that the Greek language of Homer had for the Greeks of that time”.

Sandburg also used to perform it. Lloyd Lewis saw him singing this song at a dinner party for Sinclair Lewis in 1925 and wrote about it in his article “The Last of the Troubadours” in the Chicagoan in 1929 (reprinted in Lewis 1970, p. 73/4). Now the “Buffalo Skinners” had safely arrived in circles of the progressive intelligentsia for whom it was both a reminder and a relic of an adventurous world lost long ago:

“The best singing Carl Sandburg ever did was the dinner Morris Fishbein gave for Sinclair Lewis in 1925 […]. Down at the very end of the table, opposite the host, sat Chicago’s biggest literary figure, Carl Sandburg, behind his hair and his stogy […] Somebody brought a guitar and the iron-jawed Swede stood up and, in that soft, don’t-give-a-damn way of his, sang “The Buffalo Skinners”. Everything got quiet as a church, for it’s a great rough song, all about starvation, blood, fleas, hides, entrails, thirst, and Indian-devils, and men being cheated out of their wages and killing their employers to get even – a novel, an epic novel boiled down to simple words and set to queer music that rises and falls like the winds on Western plains. […] It was like a funeral song to the pioneer America that has gone, and when Carl was done Sinclair Lewis spoke up, his face streaked with tears, ‘That’s the America I came home to. That’s it.'”

But the highlight of the song’s new life surely was Alan Lomax’ performance in the White House in 1939 for the King and the Queen of England (Gard, p. 293). “Buffalo Skinners” was also canonized by its inclusion in important Folk song collections like Louise Pound’s American Ballads And Songs (1922, p. 181) and of course Lomax’ own influential American Ballads and Folk Songs (1934, p. 390). Lomax’ classic Cowboy Songs from 1910 remained a steady seller and was published again in 1938 in an vastly expanded edition.

It also was included in at least 18 popular songbooks published between 1928 and 1950 (see the bibliography by the Fifes in Thorp 1966, p. 215/6), for example Ina Sires’ Songs of the Open Range (1928), Carson J. Robinson’s World’s Greatest Collection of Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs (1930), Margaret Larkin’s Singing Cowboy: A Book Of Western Songs (1931), the Treasure Chest of Cowboy Songs (1935) or the Lone Ranger’s Songbook (1938). Here is “The Range Of The Buffalo” from Carson Robinson’s songbook. The tune is quite similar to the one used by Lomax but the text – only six verses – is a little bit different. It’s possible that it was taken from another source but I wouldn’t exclude the possibility that this is only a heavily edited version of the variant published in the Cowboy Songs with all the melodic and textual variations brought in to avoid legal problems:

|

Surprisingly no commercial recordings of this song were made in the 20s and 30s. John Lomax himself recorded it three times in 1936, 1939 and 1941 for the Library of Congress although these weren’t released at that time. The one from 1941 – a short version with only 4 verses – is available on Cowboy Songs, Ballads & Cattle Calls from Texas (at first AFS L28 [1952] and later Rounder CD 1512 [1999], see the liner notes (pdf available at the LOC) by Duncan Emrich; a transcription is in Emrich 1972, p. 504). Popular cowboy singer Jules Verne Allen included it in his book Cowboy Lore (1931) but to my knowledge he never a made recording of “Buffalo Skinners”. Instead it happened to be Bill Bender, The Happy Cowboy who was responsible for the very first recorded version in 1939 (Varsity 5144; see Russell, Country Music Records, [Bill Bender]).

In 1945 Woody Guthrie recorded his version of “Buffalo Skinners” (here on YouTube). It was first released on Struggle: Asch American Documentary, Vol. 1 (Asch 360, 1946, later Stinson 360, now SFW 40025) and is now also easily available on different CDs, for example on Buffalo Skinners: The Asch Recordings, Vol. 4 (Folkways SFW 40103):

Guthrie didn’t use Lomax’ standard version of “Buffalo Skinners”, instead he tried his hand at “Boggy Creek” (or “The Hills of Mexico”), the cattle drivers variant from the 1938 edition of Cowboy Songs. But for some reason in a couple of verses he inserted the “buffalo” instead of “Mexico” so it’s really not clear if he is singing about cowboys or buffalo skinners. I presume he was not so much interested in these kind of subtleties but more in what he understood as a kind of “anti-capitalist” message as he wasn’t so fond of bosses. In fact this recording was first released on as part of a song collection depicting the struggles of working class Americans.

But on the other hand Guthrie also managed to modernize the text by avoiding some of the stilted language of the original: “out of work” is used for “out of employment”, “try to run away” sounds much better than “back to Griffin go”, “drunk too much” replaces “extravagant” and “starve to death […]” is a much more effective line than “I’ll even loan you a horse to ride […]”. He also dropped the last verse about coming home and ends the song at its dramatic climax when the worker’s have killed their boss and “leave his bones to bleach” on the plains.

Guthrie also used a new minor key melody that is different from those of Lomax’ and Sandburg’s versions of “Buffalo Skinners” but it works very well. Unfortunately the dreary one-chord-accompaniment doesn’t do the song justice.

Woody Guthrie’s recording was the first of many from the Folk Revival era. Most of them were derived from John Lomax’ standard version from the first edition of Cowboy Songs while some singers – like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Cisco Houston – had learned it from Guthrie:

- Hermes Nye, Texas Folk Songs (1955, Folkways FW 02128)

- Ed McCurdy, Songs of the Old West (1956, Elektra EKL 112, see amazon.co.uk)

- Raphael Boguslav, Songs From A Village Garret (1956, Riverside RLP 12-638, see this post in the fine blog Record Fiend; also available at YouTube)

- John A. Lomax, Jr, Sings American Folk Songs (1956, Folkways FW 03508)

- Pete Seeger, at first on American Industrial Ballads (1956, Folkways SW 40058) and then on American Favourite Ballads, Vol. 5 (1962, Folkways SW 40154; this is an abbreviated version with five verses, the lyrics are from Lomax’ original “Buffalo Skinners”, the melody and accompaniment are closer to Woody Guthrie; see YouTube ).

- Ramblin’ Jack Elliott & Derroll Adams, Roll On Buddy (1957, Topic 12T 105; a later live version by Jack Elliott is available on YouTube)

- Richard Dyer-Bennet, Vol. 9, (1960, Dyer-Bennet DB 09000)

- Cisco Houston, Sings the Songs of Woody Guthrie (1961, Vanguard VRS 9089)

- Carl Sandburg also recorded his version for Cowboy Songs and Negro Spirituals (1964, Decca DL 9105, see the discography at wirz.de; unfortunately this is not available on CD at the moment)

- Eric Von Schmidt, Folk Blues of Eric Von Schmidt (1963, Prestige 7717; also available on YouTube)

- Jim Kweskin, Relax Your Mind (1965, Vanguard VSD-79188, see amazon.com)

- Slim Critchlow, Cowboy Songs: The Crooked Trail To Holbrook (1969, Arhoolie 479; includes also “John Garner’s Trail Herd” and “The Crooked Trail To Holbrooke”; recorded 1957-63; see allmusic.com)

I started this with Bob Dylan, so I may also close with him although of course he only plays a small part in the song’s history. But maybe he can take the credit for bringing it to a wider audience. I presume many who saw him perform “Buffalo Skinners” in one of his shows weren’t familiar with this song. Unfortunately Dylan never recorded it officially. But it should be noted that Good As Been To You (1992) includes one of its precursors, the British “Canadee-I-O” and also Cisco Houston’s “Diamond Joe”, another cowboy song that at least owes a little to this song family. So we only have the “unofficial” recordings.

There is a private performance from 1961 – available on the so-called East Orange Tape – that is clearly based on Woody Guthrie’s version. In March 1963 Dylan used this melody for his own topical song “Cuban Missile Crisis” (recorded at the Broadside office) Then there is an abbreviated version from the recording sessions in 1967 that would later be called the Basement Tapes: here he dropped the introductory verse, forgets some of the lyrics and stops halfway through the song although it is a promising performance .

From 1988 to 1992 he performed this song at 43 concerts. Like Guthrie Dylan conflates “Buffalo Skinners” and “Hills of Mexico” and it’s never clear if it’s a story about buffalo hunters or cowboys. Again the first verse (“Come all you…”) is dropped but the last verse about coming home from Lomax’ version is reinstated. Occasionally it sounds as if he’s forgotten the lyrics and that seems to be the main reason for some – mostly minor – changes of the text: sometimes the town is Griffin, sometimes it’s Jacksboro, the year is ’73 or ’83 and at other times unintelligible. Thankfully Dylan avoids Guthrie’s one-chord accompaniment and his arrangement sounds much better and much more appropriate. Most of these live performances are very impressive and among the best versions of this song I’ve heard.

Musical Examples

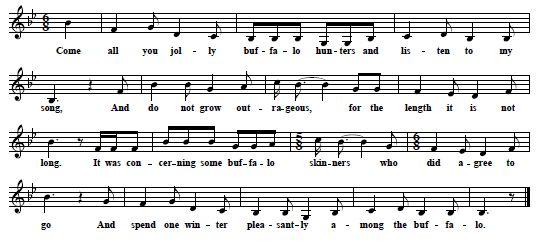

- “Buffalo Skinners”, first verse and the tune commonly used today, from abcnotation.com

- “Buffalo Skinners” or “Range Of The Buffalo”, tune and verse 2, from John Lomax, Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads, New York 1910, p.162-3

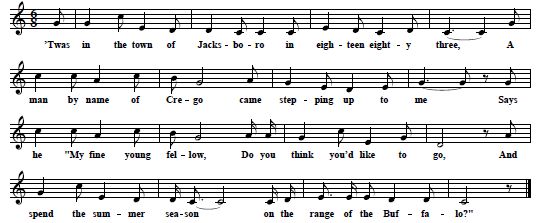

- “Canaday I O”, tune and verse 6, from F.H.E (i.e. Fannie Hardy Eckstorm), Canaday I O, in: Bulletin of the Folksong Society of the Northeast 6, 1933, p. 10

- “Michigan-I-O”, tune and verse 1, from: Franz Rickaby Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy, Cambridge 1926, p. 41-2

- “Buffalo Song”, as sung by John B. Freeman in 1941, from: J. Frank Dobie, A Buffalo Hunter And His Song, in: M. C. Boatright & Donald Day (ed.), Backwoods To Border (Publications of the Texas Folklore Society 18), Austin 1943, p. 5 (online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library)

- “The Range Of The Buffalo”, from Carson J. Robinson, World’s Greatest Collection of Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs, Chicago 1930, p. 64

Bibliography

- Benjamin A. Botkin, A Treasury of American Folklore, New York & Avenel, New Jersey 1993 (first published 1944; p. 568: reprints the two verses from Callison, Bill Jones; p. 854/5: melody and lyrics for “Buffalo Skinners” as sung by John A. Lomax himself, repr. from Charles Seeger (ed.) Resettlement Song Sheets No. 7)

- John J. Callison, Bill Jones of Paradise Valley, Oklahoma, Chicago 1914 (online at The Internet Archive)

- Norm Cohen , Long Steel Rail. The Railroad in American Folksong, Urbana & Chicago 2000

- Frank Collinson & Mary Whatley Clarke, Life In The Saddle, Norman 1997 (1963; these are reminiscences of Frank Collinson, an Englishman who arrived in Texas in 1872 and worked for some time as a buffalo hunter)

- J. Frank Dobie, A Buffalo Hunter And His Song, in: M. C. Boatright & Donald Day (ed.), Backwoods To Border (Publications of the Texas Folklore Society 18), Austin 1943, p. 1-10 (Now online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library; this is Dobie’s article about John B. Freeman and his version of “Buffalo Skinners”, most likely the original; interestingly he reports that John Henry Faulk made a recording of Mr. Freeman singing this song. I wonder if it still exists today)

- Duncan Emrich, Folklore On The American Land, Boston & Toronto 1972 (p. 500 – 505, includes words and melody of John Lomax’ 1941 version of “Buffalo Skinners” as well as a short summary of the song’s history)

- F.H.E (i.e. Fannie Hardy Eckstorm), Canaday I O, in: Bulletin of the Folksong Society of the Northeast 6, 1933, p. 10-13

- Fannie Hardy Eckstorm & Mary Winslow Smyth, Minstrelsy of Maine, Boston 1927

- Benjamin Filene, Romancing The Folk. Public Memory & American Roots Music, Chapel Hill & London 2000

- Albert Friedman, The Penguin Book Of Folk Ballads of the English-Speaking World, New York 1977 (first publ. 1956; reprints on p. 429/30 the text of “Buffalo Skinners” first published by Robert W. Gordon in Adventure Magazine, Oct. 20, 1924; this text as pdf-file for research only)

- Wayne Gard, The Great Buffalo Hunt, New York 1960 (classic book about the history of buffalo hunting)

- Emelyn E. Gardner & Geraldine J. Chickering, Ballads and Songs of Southern Michigan, Ann Arbor 1939 (online at traditionalmusic.co.uk)

- Roland Palmer Gray, Songs and Ballads of the Maine Lumberjacks, Cambridge 1924 (online at The Internet Archive)

- J. Evetts Haley, Cowboy Songs Again, in: J. Frank Dobie (ed.), Texas And Southwestern Lore (Publications Of The Texas Folklore Society 6), Austin 1927, p. 198-204 (includes the first complete version of “The Hills of Mexico”; now online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library)

- George Stuyvesant Jackson, Early Songs Of Uncle Sam, Boston 1933

- Lloyd Lewis, It Takes All Kinds, Manchester NH 1970 [1947] (online at Google Books)

- Eloise Hubbard Linscott, Folk Songs of Old New England, Mineola 1994 (first published 1939)

- Guy Logsdon, The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing and Other Songs Cowboys Sing, Urbana & Chicago 1995

- John Lomax, Adventures Of A Ballad Hunter, New York 1947

- John Lomax, Cowboy Songs And other Frontier Ballads, New York 1910 (online at The Internet Archive)

- John & Alan Lomax, Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads, New York 1938 (enlarged new edition; p. 41/2: “Boggy Creek”, this text as a pdf-file for research only)

- John & Alan Lomax, American Ballads and Folksongs, New York 1934 (online at traditionalmusic.co.uk)

- Alan Lomax, The Folk Songs Of North America, New Yok 1960 (No. 196, “On The Trail To Mexico”, p. 380, is Alan Lomax’ own adaption of “Boggy Creek” from the 1938 edition of Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads, p. 41)

- Ethel & Chauncey O. Moore, Ballads and Folksongs of the Southwest, Norman 1964 (p. 289-291: another version of “Buffalo Skinners” from oral tradition, text reprinted in Welsch 1970, p. 125/6, this text as pdf-file for research only)

- Louise Pound, American Ballads And Songs, New York, Chikago & Boston 1922 (online at The Internet Archive)

- Nolan Porterfield, The Last Cavalier. The Life And Times Of John A. Lomax, Urbana & Chicago 1996 (excellent biography!)

- Franz Rickaby, Ballads And Songs Of The Shanty-Boy, Cambridge 1926 (online available at Notendrucke aus der Musikabteilung, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

- Tony Russell, Country Music Records. A Discography, 1921 – 1943, Oxford & New York 2004

- Carl Sandburg, The American Songbag, New York 1927 (online at The Internet Archive)

- Henry W. Shoemaker, North Pennsylvania Minstrelsy,As Sung in the Backwoods Settlements, Hunting Cabins and Lumber Camps in Northern Pennsylvania, Altoona, PA 1919 (available at the Internet Archive)

- John S. Springer, Forest Life And forest Trees: Comprising Winter Camp-Life Among The Loggers, And Wild-Wood Adventure. With Descriptions Of Lumbering Operations On The Various Rivers Of Maine And New Brunswick, New York 1851 (available at the Internet Archive)

- Peter Stanfield, Horse Opera. The Strange History of the 1930s Singing Cowboy, Urbana & Chicago 2002

- N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, Songs Of The Cowboy, Estancia, NM 1908 (reprint 1989, online at Google Books)

- N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, Songs Of The Cowboys, Boston And New York 1921 (enlarged second edition, online at traditionalmusic.co.uk)

- N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, Songs Of The Cowboys, New York 1966 (reprint of 1908 edition with: Variants, Commentary, Notes and Lexicon. by Austin E. & Alta Fife; p. 195 – 214: a good summary of the song’s history; the bibliography is indispensable as it lists all published and unpublished versions of “Buffalo Skinners” and some related songs that were available at that time; a “composite text” on p. 202-206 includes a lot of variant lines from other texts)

- Oliver Trager, Keys To The Rain. The Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, New York 2004

- W. P. Webb, Miscellany of Texas Folklore, in: J. Frank Dobie (ed.), Coffee In The Gourd (Publications of the Texas Folklore Society 2), Austin 1923, pp. 38-49 (Now online available at University of North Texas, Digital Library; here we can find the first published version of “The Hills of Mexico” [p. 45, as “Boggus Creek”], unfortunately only an incomplete text)

- Roger L. Welsch, A “Buffalo Skinner’s” Family Tree, in: Journal Of Popular Culture 4, 1970, p. 107-129 (This is an interesting and helpful article. The author attempts to untangle the history of this song and draws some important conclusions. Unfortunately he doesn’t use all available variants, for example he seems to be unaware of Thorp’s book. But he discusses Dobie’s article about John B. Freeman’s version and regards it as authentic)

- George F. Will, Four Cowboy Songs, in: Journal Of American Folklore 26, 1913, p. 185-188 (online at The Internet Archive)